Roger Hawkins grew up in the tiny borough of Aspinwall on the Allegheny River just north of Pittsburgh and went on to live an adventure recorded his wartime photographs.

(Northern III Corps, early 1969)

The French rubber plantation Compagnie des Terres Rouges (Red Earth Company) in Quan Loi, 25 miles north of An Loc, was famous for the quality of its soil and the productivity of the rubber trees that grew there.

Unfortunately it was a stone’s throw from the Cambodian border and the Viet Cong who infiltrated the plantation by crossing the border at night were firing rockets rather than throwing stones. The job of securing the area in 1969 fell to the 1st Infantry Division. Mechanized units of the 1st Infantry had the same effect on the enemy as Agent Orange spraying had on the rubber trees; both eventually bounced back.

Along with US troops came their locally acquired pets, like this mutt with the good sense to hide behind the APC (Armored Personnel Carrier) driver's helmet. Here we are waiting for other APCs and a tank before entering the rubber trees in a frustrating chase of the elusive VC.

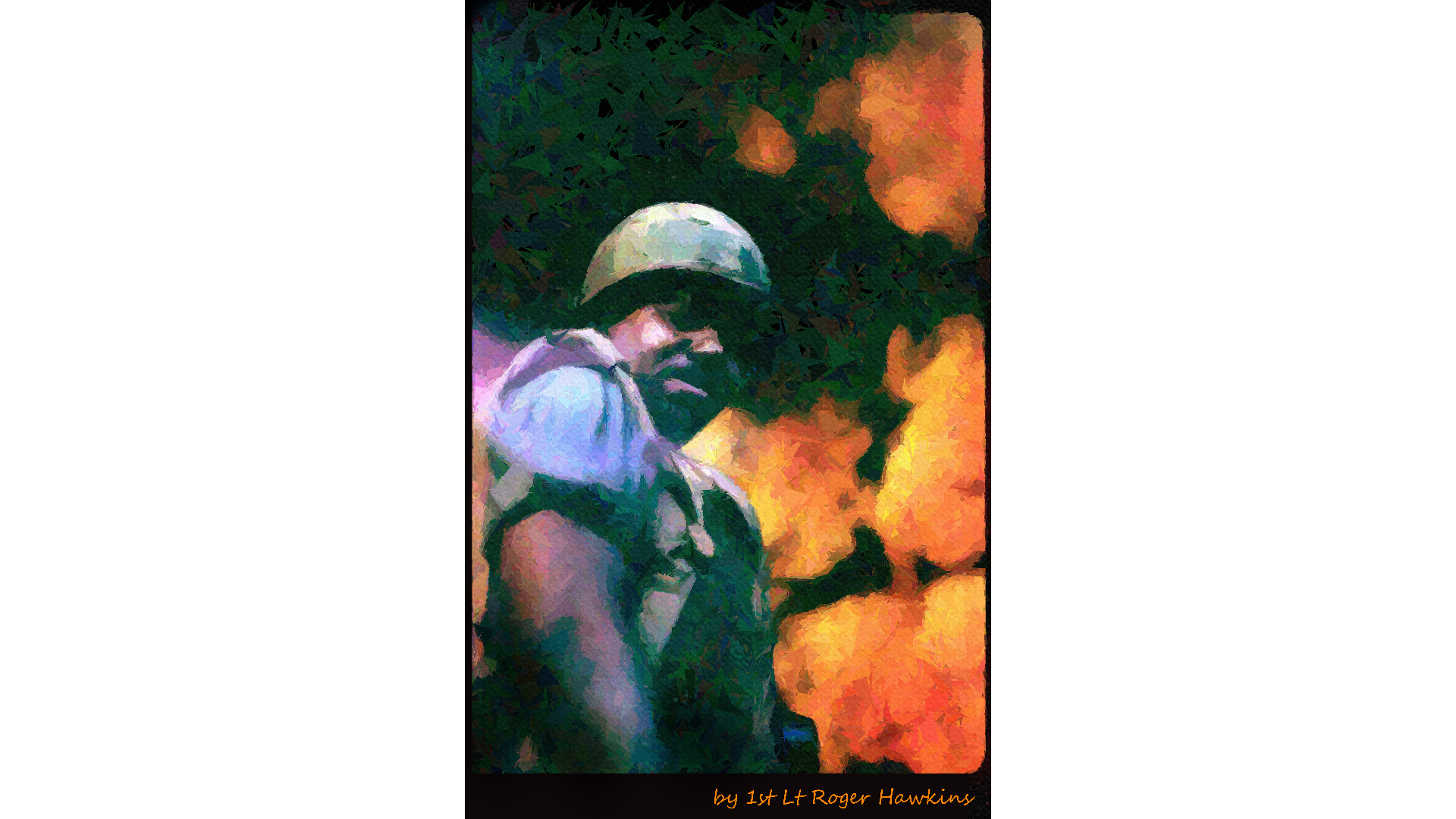

(Long Range Recon Patrol west of Anh Khe , Vietnam late 1968)

Soldiers who paint themselves green, wear uniforms stripped like tigers, and avoid armed conflicts are called LRRPs. They avoid toe-to-toe conflicts because their job is to see, report, and keep much larger enemy forces off balance.

LRRPs can move unseen and leave little sign because they travel lightly armed in six or seven man teams. I had asked LRRPs from the 173rd Airborne located in An Khe if I could accompany one of their missions expecting to be turned down. Without batting an eye, they said "yes" and took me through the intricacies of immediate action drill (a method of breaking contact with an enemy) and then down to the range to see if I could shoot. I could.

The next morning I was on a helicopter flying into the hills west of An Khe. The doors were off and a soft light permeated the interior of the aircraft. The turbines powering the Huey helicopter were too loud for sustained thought let alone sustained conversation so I could not ask what the trooper next to me was thinking.

However, I could tell from his look that he had retreated into his personal space to deal with what might lie ahead. With my camera I captured the smoke grenade on his shoulder, paint on his face, and the thousand-yard-stare compressed into the six feet of the troop compartment.

A helicopter carrying a LRRP team from the 173rd Airborne Brigade and myself hopped from hilltop to hilltop. We couldn't hide the helicopter from anyone watching so we played a version of the shell game forcing potential watchers to guess which of our landings was the real one.

I had already agreed with the patrol that I would be the first one out so I could get pictures of the rest of the team jumping off the skids. The thought that, if we were hit, the pilot might leave me really tied my stomach in a knot. The chance of being killed was frightening. The possibility of being left behind was worse.

Thankfully things were happening fast, after I hit the ground I only had time to click the shutter twice before the whole team was on the ground with me and the aircraft was nose down tail up and climbing for altitude.

Our first priority was to get as far away as fast as we could from the landing site (actually not a landing, but a brief hover). I was an officer and the team was enlisted but I had no authority and no vote. I followed, photographed and kept my mouth shut and let the pros do their work. They were in shape and I was not, so as we climbed the only thing occupying me was breathing, climbing, and sweating.

I was sure I was already dead from exhaustion when the team leader, Sgt. Sylvester Brocatto, announced we had reached the Promised Land and we all slumped down in the jungle, our new home. Then nothing happened. We sat there all day till the sun faded. We sat motionless in the dark for hours.

Suddenly there was a glimmer of flashlights in the valley; fifty more or less. The Sgt pulled me under a poncho along with a compass, map, red flashlight to protect our night vision and a radio hand set. He worked out the target coordinates and called them into a firebase 15 miles away.

Shortly we heard what sounded like a supersonic school bus tumbling end-over-end fly over the top of our hill and burst in an orange ball of flame in the pitch black jungle. The Sgt thought it looked on target (but distance is deceiving when you can't see your hand in front of your face) so he whispered again into the mike and said, "fire for effect." Soon a lot more hell rained down on the jungle and our job was done.

The "duster" was already an antiquated weapons system when the Vietnam War started. It was designed around a set of 40 mm Bofors guns mounted on a tank chassis and used as antiaircraft artillery, but it did not shoot high enough and fast enough for modern wars and didn't have the tracking technology needed for the later part of the 20th century.

But point a duster at soft targets like enemy troops or vehicles and you had the best weapon in the shooting gallery.

This Duster looks uphill into the ominous and brooding jungle that flanked highway 19 stretching from Qui Nhon to Pleiku. The guns could theoretically fire 240 rounds per minute and reach out 9,200 meters. However, the 40mm tracer ammunition used for ground support in Vietnam self-destructed at 3,500 meters for the safety of unintended terrestrial targets in the distance.

(23 May 1969 Operation Lamar Plain in the mountains west of Tam Ky Vietnam)

Elements of the 101st Airborne (Air Mobile) were in close contact with a dug in enemy unit. I had used up 10 rolls of motion picture film and had switched to my still camera. The official report reads as follows:

"At 10:00am D/1-501 joined the bitter fighting by engaging an enemy force in the area. The fighting continued throughout the day as the enemy tenaciously defended from steel-reinforced concrete bunkers. Tactical air, artillery and Air Cav support was used throughout the fighting but the ground units remained locked in close combat throughout the afternoon. As the elements disengaged the enemy left 25 KIA on the battlefield with the 1-501 suffering 12 KIA and 46 WIA in the fight."

Shortly after this photo was taken, I also expended the last of my still camera film and decided to shoot bullets instead of film.

Cameramen were only issued pistols for self-defense, but I had borrowed an M-16 before dropping into this fight. I never had a chance to test it. I set my weapon to automatic, popped my head up over the berm on this rice paddy and pointed my M16 into the tree line and pulled the trigger. I felt the kick of a single recoil. I ducked back down pulled the receiver and could see the butt end of a spent shell jammed in the chamber.

The trooper next to me pointed me at the machine gunner and indicated he had a cleaning rod. I crawled down the line to the machine gunner and used his cleaning rod to clear the weapon. I popped up again for a second shot and had the same result.

On closer inspection I could see the cartridge extractor was broken. What to do? I crawled further down the line to the platoon leader and offer my services in any capacity he saw fit. He asked if I would take the walking and crawling wounded to the rear which I did.

I put myself at the back of a line of five wounded to make sure none of them fell by the way side. The worst of the wounded had been shot in the ass with the bullet exiting near his hip. His main concern was the family jewels which were dangling from his torn pants. Since I was crawling right behind him I was able to assure him that they still looked serviceable.

I had been crawling through the soldier’s blood trail and when we got to the rear my head was bloody. A medic ran up to me and wanted to treat my head wound. I assured him I was fine, but he persisted. I realized the medic's hearing was compromised by artillery and bombing so by pointing, gesturing and yelling I got him directed to the guy with the bullet in his rear end.

I would be going home in June or at least I hoped I would if I didn't do too much more of this.

The M48A3 Patton Tank saw limited service in Vietnam due to the steep mountains of the Central Highlands and the swampy canal-crossed marshes and rice paddies of the Mekong Delta. There were no sweeping envelopments by tank battalions in the style that Gen. Patton so loved in WWII.

Instead they were often used as static strong points that could be move around by road when needed.

This one is reinforcing a group of "Dusters" (40 mm tracked guns) guarding the east-west Highway 19 between Pleiku near the Cambodian border and Qui Nhon on the coast. Placed in the Mang Yang and An Khe passes, these teams of tracked vehicles could dominate the sections of the road where civilian and military traffic was most vulnerable to attack.

As important as the main gun on the tank was the search light hidden behind the protective covering decorated with the skull and crossbones. That search light directed fire from the "Dusters" by pinpointing enemy formations during night attacks.

“War is like an aging actress: more and more dangerous and less and less photogenic”. – Robert Capa (father of modern combat photography.)

I always liked Robert Capa's photography and wanted to emulate his career, except for the part where he died from a land mine in Vietnam. The action after this photo could have cost me my life.

This was my second day in the field with D company 1/502nd. The night before I had slept on the cardboard of a used ration box, so even before the morning started things were not going well.

As we started to move the company commander called in artillery where we slept the night before to make sure there was nobody following who could shoot down on us. However, the barrage arrived before everyone was clear of the hill and some of our people were struck by friendly fire.

Then as we moved down the hill our lead elements started to take fire from a well-entrenched enemy beyond the rice paddies at the bottom of the hill. After the people in this photo ran on down the hill and crossed the rice paddy, myself and an M79 grenadier were the last two people left.

I noticed that when the grenadier fired the enemy machine gunner tended to go silent for a few moment. When he fired I got up and ran down to the rice paddy and ran along the top of the berm until I hit a muddy spot and fell flat on my face. I was in the open and my only option was to play dead.

With one eye I watched an ant crawl up a blade of grass an inch from my face. The thought came to me that my best chance was to wait for the next thump from the grenade launch and then jump up and continue.

Thump! That was my cue and I ran with long strides and my knees coming half way up to my chin. I made it to the dike on the far side and a soldier turn to me and said, "We thought you were dead."

"I thought so too," I replied.

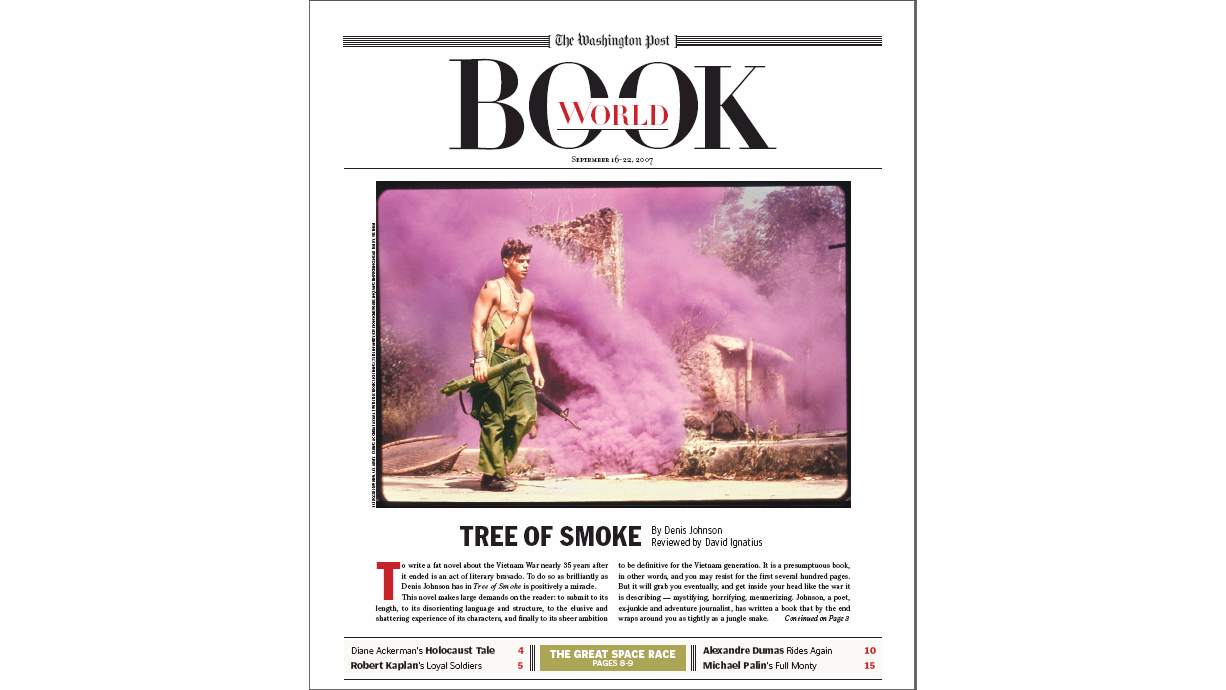

Thirty-eight years after photographing the 101st Airborne Division on operation Lamar Plains in Vietnam I am sitting in my home office and the phone rings. It is the art director for the Washington Post book review and she says she wants to use one of my photographs on the book section's September 16-22 review by Denis Johnson of David Ignatius' Vietnam novel "Smoke Tree."

Of course, I willingly agree even though the novel says nothing about the battle that generated the photo. It did not describe climbing a hill with artillery powder transport tubes filled with ice cream for delivery to troops in a fire fight. It was a well-intentioned gesture by cooks in the rear area, but after carrying it up a hill in 106° and 99% humidity, finding out that the powder residue poisoned the contents and then passing out from heat in the middle of a firefight after the effort, I had a different perspective on Vietnam than the one presented in the book.

I woke up laying on the veranda of an old French plantation in the middle of a raging battle with a medic pouring water and salt tablets into me and against the medic's protests picked up my camera and went to work documenting the confusion around me.

As the company commander talked in Air Force F-4s dropping their ordnance dangerously close, D Company troops popped purple smoke to mark our position.

The air cover tipped the battle in our favor and as the battle began to wind down troops began to leave the safety of cover. At that moment a trooper carrying a LAW (Light anti-tank weapon) and his M16 walked in front of the purple smoke not knowing I had just given him anonymous fame that would be delayed 38 years.

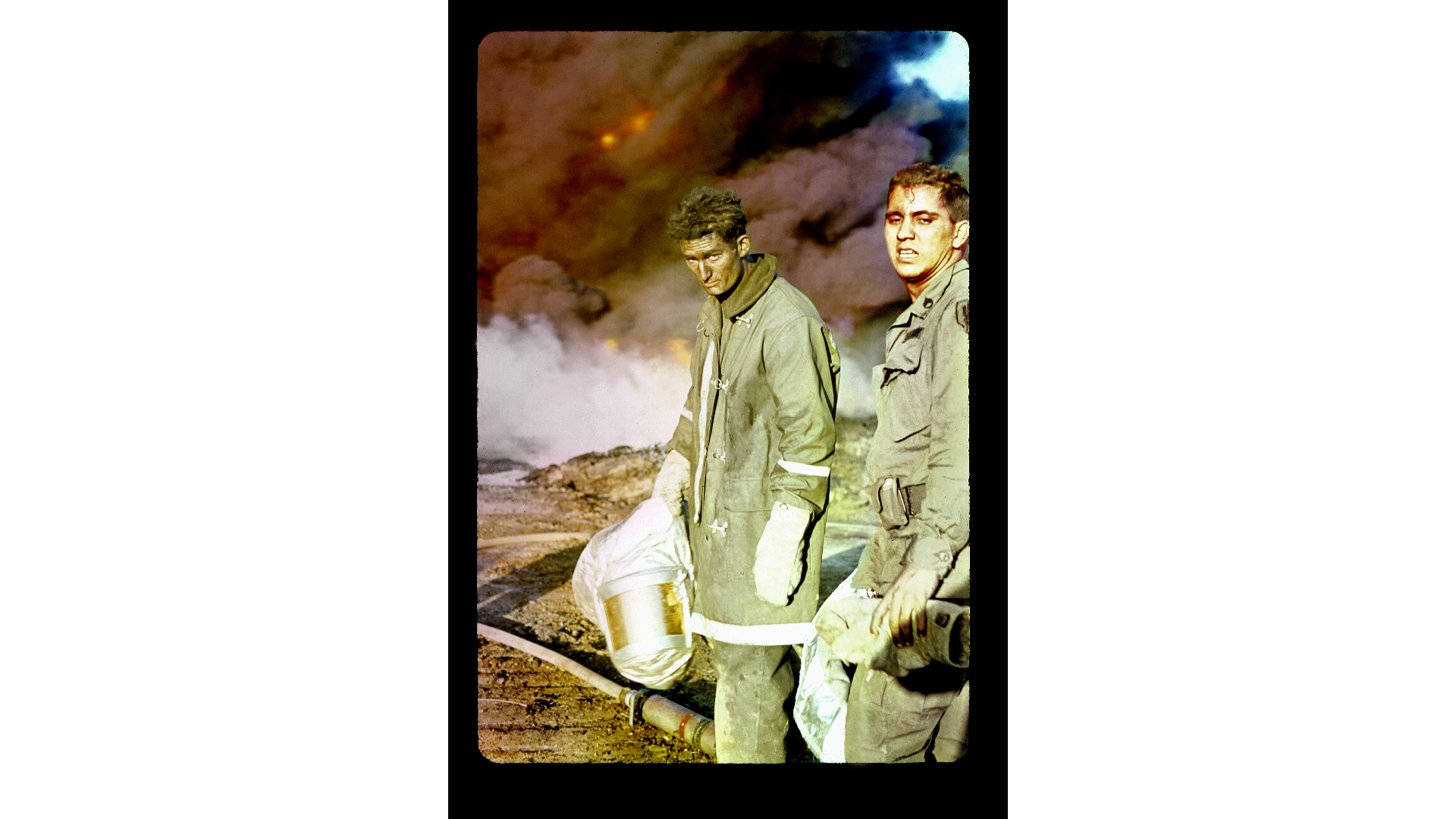

Camp Radcliff near An Khe, Vietnam (Late 1968 or early 1969), enemy sappers breached the perimeter wire and VC rockets hit the POL (Petroleum Oil and Lubricants) dump setting fire to about an acre of stacked oil drums.

Camp Radcliff near An Khe, Vietnam (late 1968 or early 1969), enemy sappers breached the perimeter wire and VC rockets hit the POL (Petroleum Oil and Lubricants) dump setting fire to about an acre of stacked oil drums. Night photography would have been spectacular, but at Detachment A, of the 221st Signal Company we received orders to hold in place as a group of enemy combat engineers was known to be running loose in the dark and American troops were likely to shoot anything that moved.

By early morning we were able to get to the dump. Firefighters from the airfield were already on scene spraying fire retardant and using bull dozers to raise a dam to contain the burning oil.

Fifty gallon drums were exploding, sending the flaming steel cylinders high into the air. It was an unpredictable and highly dangerous environment. The firefighters wore aluminized heat reflective helmets, but just standard fire coats.

The bull dozer operators were burning their hands as the metal controls on the giant machines started to heat up. My photographer and myself had no special protection our hands and faces and we could only stay close for second before running back for cooler air.

The sergeant in charge of the firefighters wanted us out but we also had a job to do. I yelled "sergeant" and kneeled down so he would be framed by the raging flames as he turned toward me.

Today I found a recipe for foiled hot dogs: Spread each hot dog bun with 1 t. mayonnaise. Place one piece of American cheese in each bun and then place one hot dog on top of cheese. Spread 2 t. pickle relish on top of each hot dog. Wrap each hot dog combo in foil, crimping the ends and edges. Bake for 30 minutes in a 350 degree F. oven.

Well these firefighters had been fighting an oil fire with a temperature of 1,960º F with their heads wrapped in aluminized heat reflecting helmets for about eight hours. It was a job no one would relish.

It started when a group of VC infiltrators managed to light up the POL (Petroleum Oil and Lubricants) dump at Camp Radcliff in An Khe, Vietnam. After eight hours in this hostile environment the fire was contained but it was impractical to fully extinguish it so the decision was made to let it burn itself out. A week later the ground was still hot.