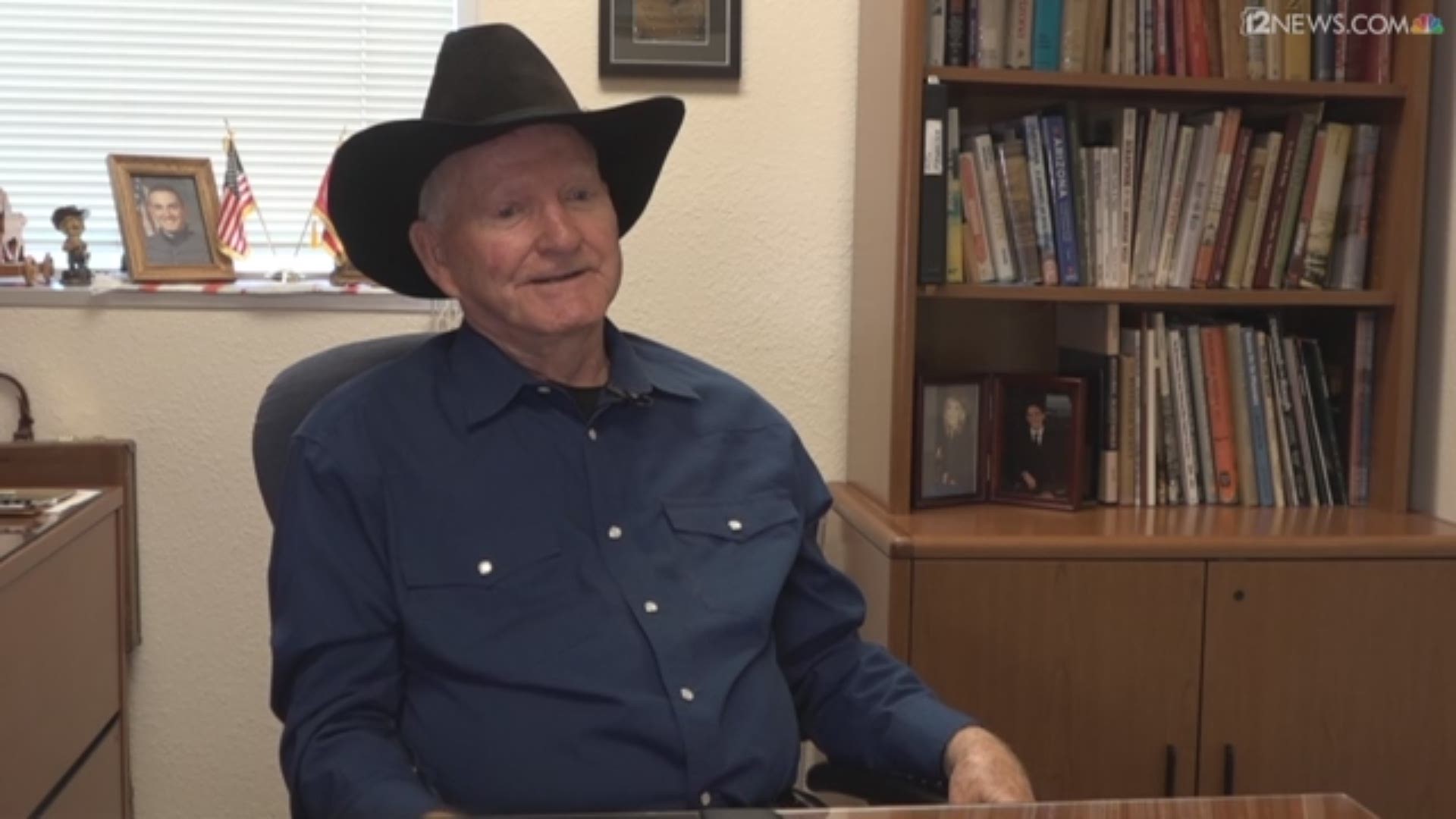

In Arizona, everybody has a story.

The state’s official historian will tell you that Arizona’s diversity is one of its best qualities.

Arizona is “like an amalgamation,” Marshall Trimble said. “You melt something together and it’s stronger.”

To Trimble, Arizona is “diverse everything.” From its geography to its people, we thrive on it here in the Grand Canyon State.

And for a man who taught Arizona history for four decades, his seemingly never-ending supply of stories offer a small window into a past that shaped the state and culture we know today.

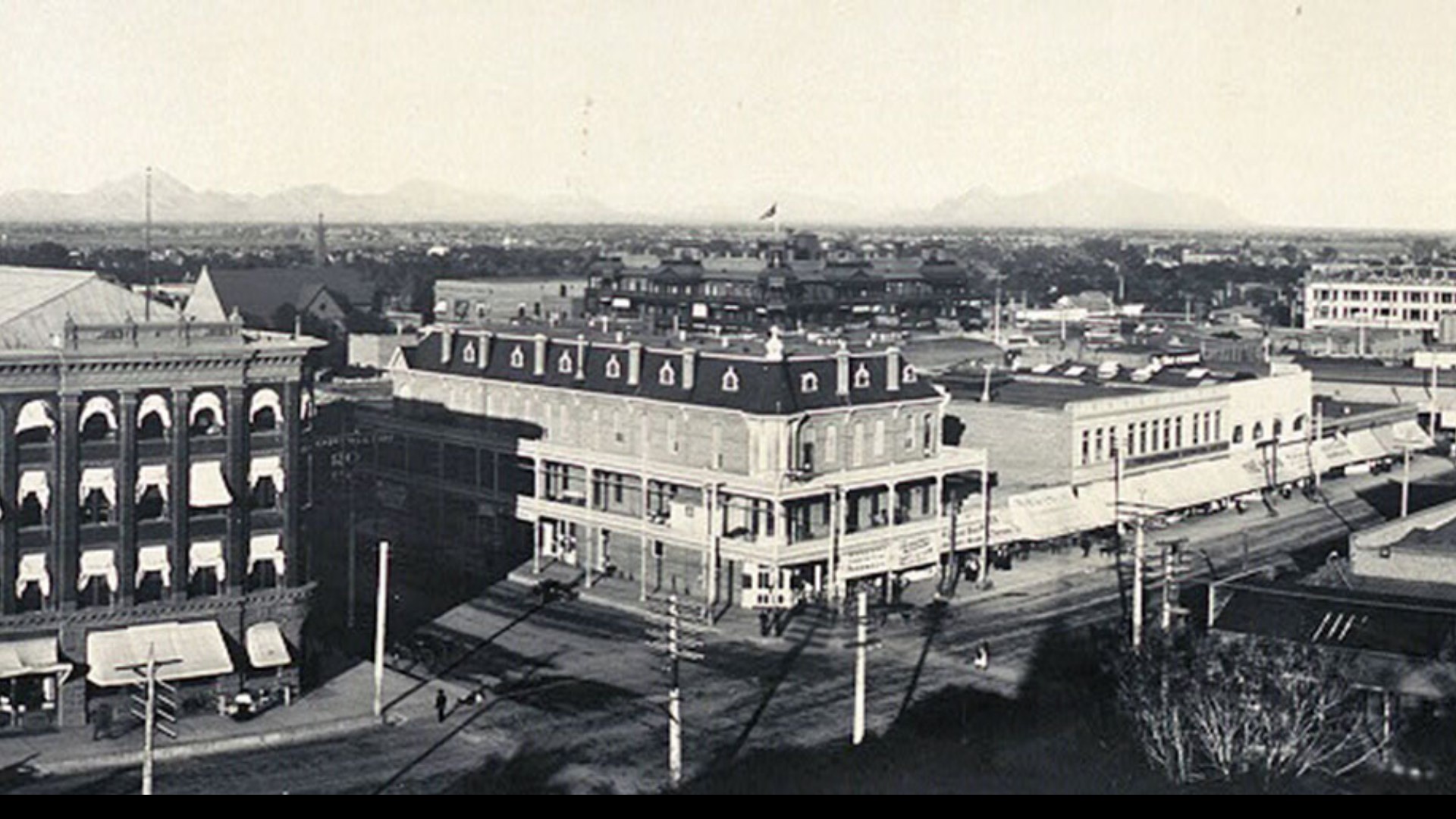

The territorial days

A treaty officially ended the Mexican-American War and forced Mexico to give up over half of its territory, which included parts of present-day Arizona. Years later, the United States would acquire a region of what would become present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

By then, Trimble says there was a small presence of people here. Tucson had shrunk to about 500 people, a lot of which chose to return to Mexico while those who stayed were at the mercy of the Apache.

“This becomes Arizona’s story in those early days,” Trimble said. “They were just out here on their own.”

But in the early days of Arizona through the 1860s, Mexicans were in the majority, Trimble said.

“The exchange value, dollar exchange, was pesos instead of dollars,” Trimble said.

Spanish was the main language in those days and a shortage of, “so-called white women,” resulted in interracial marriages and a society that ultimately got along “really well together.”

“All the upper class both Mexican and Anglo got along just fine, they socialized together, they intermarried,” Trimble said.

“The railroads changed everything”

After the arrival of the railroads, Trimble said the whole society changed.

English began taking over as the main form of communication and the demographic changed as Mexicans dropped from the majority.

Around 1880, Chinese families established themselves in Arizona working on the railroad in the southern part of the state.

“They were better than anybody else [at working],” Trimble said. “They seemed to be immune to all the diseases.”

And when the railroad was finished, the Chinese families moved up to Phoenix where they established restaurants and other businesses.

Feeling they were slipping, Trimble said the Mexican population formed an alliance in 1894 for equal treatment.

“You may out number us now, but we were here first…kind of a thing,” Trimble said.

And the society that formerly got along so well with each other no longer did.

“All that cordial stuff that went on during the early days kind of went away,” Trimble said.

The Mexican population remained strong in the Arizona territory because of several old, powerful families in places like Tucson and Yuma.

That lasted until about statehood, Trimble says.

Arizona’s statehood

After Arizona officially became a state, people began to pour in, Trimble said.

Phoenix went from a “small little place” to the largest city in the state by 1920. Before places like Bisbee, Tombstone or Tucson always held that title, Trimble said.

“And Phoenix never looked back,” Trimble said.

The Mexican Revolution, which started in 1910, was also taking place during this time.

Trimble said it’s estimated more than a million Mexicans immigrated to the United States, “just to escape the revolution.”

Two world wars and a Great Depression

Just two years after Arizona became a state, the “Great War” began. The war, Trimble, said created a big “man-power” shortage.

“All the men had gone off to Paris,” Trimble said.

Workers were needed in the farms and in the mines. Mexicans were welcomed in.

When the war ended four years later in 1918, a post-war depression hit and Mexican workers “weren’t welcome anymore,” Trimble said.

Trimble said they were “encouraged” to go back to Mexico. And when the Great Depression hit, immigration was really discouraged.

“The jobs were few and they wanted them for American citizens,” Trimble said.

A lot of the Mexican population in Arizona went back to Mexico. But by World War II they were needed again to work on ranches, farms and in the mines. And some of them even joined the service, Trimble said.

The labor shortages brought on by World War II resulted in the creation of the Bracero Program, which was created in 1942. The program was established through a series of agreements between Mexico and the U.S. allowing Mexican men into the country to work.

An estimated two million men entered the U.S. on short-term labor contracts between 1942 and 1964.

During the war, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order, which sent more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans to internment camps.

Arizona had two camps with some of the largest populations among all of the camps. Between Gila River and Poston, Arizona held over 30,000 Japanese-Americans. Poston had the second largest peak population of any camp, behind Tule Lake in California by less than a thousand.

"At Gila, there were 7,700 people crowded into space designed for 5,000. They were housed in mess halls, recreation halls, and even latrines. As many as 25 persons lived in a space intended for four," an excerpt from Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians read.

Both camps closed in 1945, and according to the National Archives, while some of the Japanese-Americans who lived in the camps returned to their hometowns, others “sought new surroundings.”

Right up to World War II, Trimble said, you had two classes within the Mexican population. There was the ricos (rich) and the pobres (poor).

“You were either a rich, prosperous Mexican or you were working the fields for bad wages or working in the mines for lower pay than the Anglo workers got.”

That changed after the war and a lot of the reason it did, Trimble said, is when Mexican-Americans came home from the war they realized they were respected more and “better loved and better treated in Europe.”

“There’s something wrong with that picture when you’re America, the land of the free,” Trimble said.

Civil Rights Movement

Trimble grew up in Ash Fork a small town in northern Arizona along old Route 66, and said he wasn’t exposed to much of the segregation going on until he moved down to Phoenix in the late 1950s.

“We were mostly Latino and Anglo types and we played ball together, we bunked together on trips,” he said. “It was the way it was. We all had grown up together.”

Trimble says a 1900 census showed there were fewer than 2,000 African Americans living in Arizona.

According to Trimble, Booker T Washington made a trip to Phoenix in 1911 and, although he didn’t deny there was racial prejudice, he was amazed by Phoenix and how its diverse population got along together.

Washington said it was a “melting pot” of people, Trimble said.

After Arizona became a state, only two laws addressed the topic of segregation, according to a report from Phoenix’s Historic Preservation Office.

One of those laws prevented “intermarriage between persons of Caucasian blood and their descendants with Negroes,” while the other law “provided for the establishment of segregated elementary schools.”

According to the report, the “only structure in Arizona’s history” built to be used as a black high school was Phoenix Union Colored High School, which opened in 1926. It was changed to George Washington Carver High School in 1943.

Arizona desegregated its schools a year before the landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, in 1954 Trimble said.

Just a few months before the signing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a speech at Arizona State University.

“No section of our country can boast of clean hands in the area of brotherhood,” King said to the crowd.

But even after the Civil Rights Act there was a “de-facto segregation” going on in Phoenix, Trimble said.

“That has changed,” Trimble said. “But it took a long time.”

Arizona would become one of the last states, nearly six years after the first King holiday was observed, to officially recognize Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a national holiday, and the “only one approved by voters,” Trimble said.

The first state King holiday was observed in January 1993.

Today and the Arizona of tomorrow

In 1980, Latinos made up 16 percent of the population in Arizona, according to research by Arizona State University’s Morrison Institute of Public Policy.

Today, that number continues to grow.

According to recent U.S. Census Bureau data, Latinos make up more than 30 percent of Arizona’s population and are expected to take over as the majority sooner than you might think.

The state could reach majority-minority status as soon as 2030.

“Arizona’s going to be very Latino, and that’s not a bad thing at all,” Joseph Garcia, director of Latino public policy at the Morrison Institute for Public Policy, said. “Arizona’s always been Latino.”

Trimble says Arizona has been “painted with a broad brush about a lot of things,” often making national headline for acts deemed racist.

Bad news spreads, Trimble, who says he always balanced negative stories about Arizona with positive ones to his students, said.

The biggest in recent years would probably belong to SB 1070 aka the “show me your papers law,” one of the nation’s toughest bills on illegal immigration, or former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose racial profiling was well-known across the country and eventually led him to be found guilty of contempt of court after refusing to stop on a judge’s order.

Garcia said SB 1070 “resulted in a black eye, self-inflicted black eye that Arizona got nationally and even internationally.”

Arizona is not without it prejudice, but Garcia said it has learned from decisions like SB 1070.

“If you notice, there’s not a lot of strong, hard-line anti-immigration laws coming out of the state legislature, and the reason is because we’ve learned that lesson,” he said.

And as Arizona experiences a major change in demographics first, Garcia has hope the state will “right the course.“

Trimble realizes the state he loves so much isn’t perfect.

Arizona has always been home for the historian and he’s lived here long enough to see the good, the bad and everything in between. He said he’s seen race relations in Arizona change but says it needs to change even more.

“You see people getting along, especially young people,” Trimble said. “That makes the future look brighter, I think.”

Because without such diversity, heavily shaped by the Latino and Native American cultures of the past, Trimble said, the Arizona we’ve come to know wouldn’t be what it is today.

“I think we’re all richer because of it. I think there’s not a question about it,” he said. “Everybody has a story.”